Tariffs: The Curse from Hamilton

Protectionism always doubles back to its rootes in the flawed Hamiltonian-Clay American System

Donald Trump and the “America First” Republicans have a problem with free trade. Trump, since 2016, has decried a trade deficit with China claiming it as a chief problem. Thus began the Trade Wars. In March of 2018, for example, the Trump Administration imposed 25% tariffs on steel imports and 10% on imported aluminum.

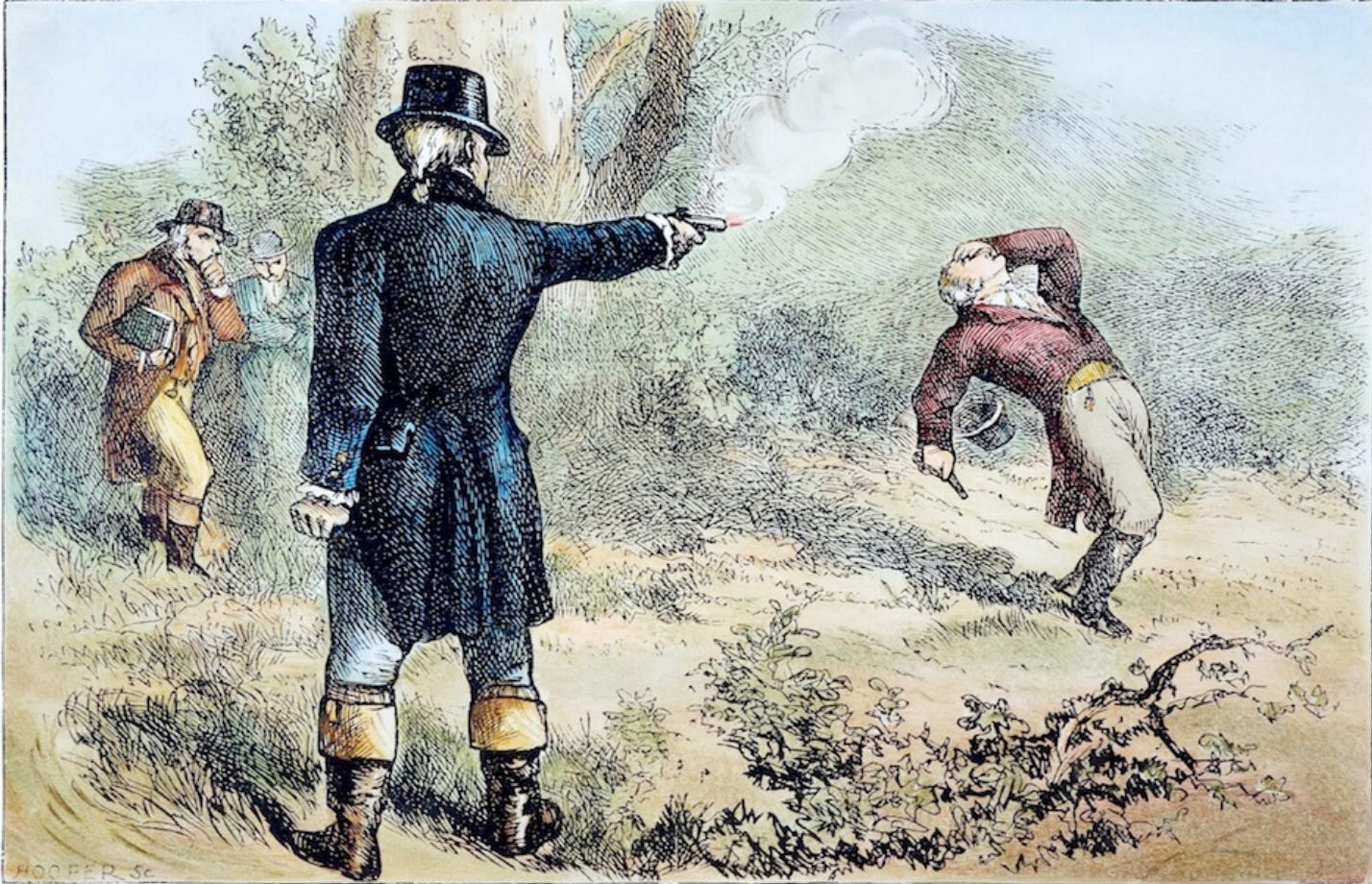

Trump’s ideological fixation on tariffs in the name of protecting American jobs and manufacturing is hardly new to America. Donald Trump is not the origin of ideological protectionism in America. Hamilton was king of protectionism in early America: believing in tariffs to protect domestic manufacturing and internal improvements. Henry Clay followed soon after with his American System as the Whig ideological mission. Whilst radicals like Andrew Jackson and Thomas Jefferson attempted to fight back against this mission it largely reigned throughout much of American history, benefiting cronyist businessmen at the expense of Americans.

Trump has continued on his anti-Free Trade crusade to cater to a populist base. Recently he has come out in favor of tariffs as high as 60% against Chinese imports. This is problematic to anyone in favor of any form of free enterprise and trade. Long has the lie been used that protectionism will promote domestic business, and it must be dismissed time and time again.

Laffer Curves and the Fallacy of Revenue vs. Domestic Production

Historically the case for protectionism on purely economic grounds is one of either fiscal revenue or “infant-industry” analysis. The first if that tariffs and other protectionist measures must be levied to bring in revenue for the government. Infant-industry analysis holds that growing industry cannot spring up in one’s country because of entrenched foreign competition.

The logic behind infant-industry analysis is that the government must prevent foreign competition while these new producers grow so they might compete. But this is contradictory to the first argument. If the priority of the government is to collect revenue, there is a point in which it is maximized. Tariffs must then be low enough to allow imports to enter but high enough to extract revenue. This analysis is called a “Laffer Curve” after Artur Laffer. Laffer theorized there to be a maximal rate of taxation on a good that maximizes revenue, any taxation above that rate will result in decreased revenue as consumers/producers will shift their activity from that activity.

If one hopes to extract revenue they must find this careful spot as a policy maker that doesn’t dissuade foreign trade so much that there is no revenue. The infant-industry enthusiast wants quite the opposite. Either they simply dissuade consumption of foreign goods or they collect the optimal amount of revenue. The two cannot exist together.

Building Industry on Foundations of Sand

Discarding with revenue collection it is best to address the infant-industry argument head on. The argument follows, as above, that domestic manufacturing is unable to properly compete with foreign competition and thus tariffs should be enacted to enable new firms competition with foreigners.

The theory relies on tariffs raising the price of foreign goods so domestic manufacturing that otherwise would be unprofitable are able to establish themselves to compete. The tariffs explicitly acts to raise the price of the foreign goods, this poses many problems that will be addressed later.

Firms engage in production with an anticipation of a future market price. There is uncertainty here, as the market price may change over time, but there is an assumption of future demand for a good or service. The entirety of demand for higher order goods, labor, and land are determinant on the expectation of a future market price. Inputs will only be demanded at certain prices if the return on the market is expected to be more than the totality of the costs of the inputs per goods.

If the assumed future price is correct, or even higher, the company will profit. If it is incorrect, being lower, then the costs will outweigh the price and losses will occur. The assumption about a future price will dictate the demand for land, labor, and capital by an industry.

When tariffs push up the price for a foreign good, domestic manufacturing will make assumptions about the market price in their demand for inputs. In the past these manufacturers must have assessed that the future price, before a tariff, would have resulted in losses if they demanded land, labor, and capital. With the tariff in place, the manufacturers make other assumptions. Manufacturers will demand these higher order goods and labor at their higher prices domestically, because they anticipate this higher price.

So tariffs certainly will spur more manufacturing of that good, but it lays a weak foundation for that industry. The assumptive market price isn’t identified only by one manufacturer but many. Profits attained by one business are noticed by others who soon enter the fray. Competing for the land, labor, and capital that allows for such a profit will raise their costs. This whittles away the profits for the manufacturer. Their firm soon loses profitability that spurs manufacturing.

But often there is no window for the imposition of the tariff. It simply becomes in perpetuity, and the resources that might go to more efficient production instead go to rent seeking. Subsidized profits become the norm and resources are wasted where they might not otherwise be. That brings us to the next and final point.

Market Distortions and Harming Domestic Manufacturing

Tariffs spur into motion production that would otherwise occur. By raising the price at which the firm anticipates it can sell its product, it causes those firms to bid for more capital, land, and labor. They drive up prices of those higher order goods when they might otherwise have gone to other ventures that anticipate true market prices. This is a distortion of the market.

What would have otherwise been other uses of that labor, land, and capital towards more productive and profitable projects, is now shifted to a subsidized industry. If that might be the production of further higher order goods, that eventually would become a consumer goods, it goes further in what it prevents. It distorts what the most efficient use of goods and resources would be otherwise.

Further, by discarding with cheaper foreign goods, now the industries that made us of those goods in their own production are harmed. Hardly any consume steel or aluminum for its own sake, rather they are higher order goods. By making them more expensive, it might aid domestic manufacturing of that higher order good but harm the manufacturing that uses them. Consumer goods are not the only goods taken in by Americans from abroad. By making the higher order goods arbitrarily more expensive, through preventing foreign competition, it will hurt those other firms.

A firm that produces using these goods must now pay more for that good. They must now either offset those costs, raise their prices, or go out of business. Tariffs just stand to make life worse off for all at the expense of one business.

The Hamiltonian System is hardly American—it is mercantilist. It does not serve the interests of the common man in the United States, it makes their conditions worse. It distorts the real demands of the markets by favoring one, often politically connect, industry above the others. It does not bring in revenue if it meets its other purported demands. It does not even serve this manufacturing long run. It is better to allow an interconnected world where all are made better off. It always reeks of rent-seeking and cronyism.